John Young Architect http://jya.com/jya.htm

The Architectural Forum, Jan/Feb, 1970, pages 72-77.

By Adele Chatfield-Taylor

Miss Chatfield-Taylor has been very much involved in this project. She did extensive research into Paterson's architectural history, and she is member of Urban Deadline. She expects to receive her M.A. in the Restoration and Preservation of Historic Architecture at Columbia University.

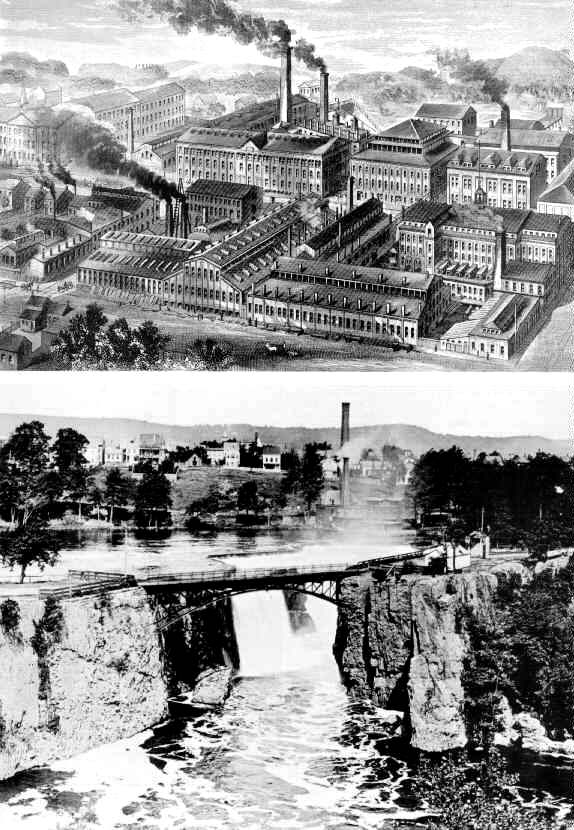

An 1872 rendition of the "Rogers Locomotive Works" (above, top) depicts a prosperous Paterson, and illustrates the complex architectural requirements of mid-19th-century industry. The Great Falls of the Passaic (above, bottom) were the original incentive to industry raceways provided water power for the first mills and factories, and then steam enabled manufacturers like Rogers to expand inland, independent of the river.

If you've ever been to Paterson, New Jersey, chances are you didn't go there to see the oldest urban industrial experiment in the United States. Or, if you live there, chances are you do not know that Paterson was once intended to be the country's "National Manufactory." Or you don't care. For you must first deal with what Paterson is today: another American city in the grip oF urban decay.

There is nothing unique about present-day Paterson -- it has the universal problems of pollution, racism, poverty, unemployment, and old politics -- but there is something unique about an ailing 19th-century city that still has its 180-year history intact. When major industry moved out fifty years ago, and the homeless and jobless moved in to remain ever after, the physical part of the city stayed as it was and the rest of the city spoiled around it.

The city can be repaired with standard urban renewal finesse -- raze it and rebuild it -- or destroyed by spontaneous combustion like Detroit in 1967, but it probably won't be, since Paterson cannot afford it and neither can Nixon. So Paterson is considering a proposal for renewal that has been presented by a group known as Urban Deadline. The renewal is designed to be a self-help project, and thus must also be self-made; Urban Deadline has provided the general outlines and the people of Paterson will supply the specifics. The proposal is based on the belief that Paterson will discover a means of treating the present -- which makes renewal necessary -- by reclaiming the past, which gives the city a purpose and precedent.

The proposal recommends the preservation, rehabilitation and continued use of historic industrial architecture, and the development of city-owned land and the frontage along the Passaic River. It will provide new public recreational facilities, a new source of employment, and new revenue for the city. It is intended to demonstrate that the physical evidence of Paterson's distinguished history can be salvaged to become the focus of a comprehensive renewal program.

Paterson was founded in 1791. Earlier that year, Alexander Hamilton had presented to the House of Representatives his Report on Manufactures, showing that the United States needed to develop its own industry (previously forbidden by the mother country) in order to be totally independent.

To put his theory into immediate action, the then-Secretary of State joined the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures (strangely shortened to SUM), an organization formed to initiate large-scale industrial activity in the state of New Jersey. Due largely to his interest and encouragement, the SUM was New Jersey's first business corporation and in its charter was given a unique set of powers, including exemption from state and local taxes. The SUM's ambition was to manufacture everything.

The Society chose for the seat of its enterprise the Great Falls of the Passaic River -- a 70-ft. waterfall that was an astonishing sight even in the comparative wilderness of the 18th century and that remains Paterson's most spectacular attraction. They bought over 700 acres of land and named the place Paterson after the governor of the state.

After choosing the site, the most difficult task before the SUM was harnessing the Passaic. At Hamilton's recommendation, but not without some hesitation, the Society engaged Pierre Charles L'Enfant to plan the waterways and lay out the town. The impetuous L'Enfant, engineer-planner-architect, was available only because he had been freshly fired from his post as planner of Washington, D.C. -- he had proven himself l'enfant terrible by spending, in his first year at the nation's new capital, more than the entire budget for the city, and by insulting everyone in town including the President and Hamilton himself.

L'Enfant was hired at a particularly unfortunate time for the SUM. The governor of the Society, William Duer, had been disgraced and imprisoned in the New York panic of '92; half of the SUM funds had been lost in the shuffle; and superintendents who had been hired prematurely to manage the nonexistent mills remained on the payroll.

Characteristically for L'Enfant, he plunged in with great energy and grand ideas. He planned a five-mile aqueduct and a city of radiating spokes, but construction had scarcely begun when he was again banished for his extravagance -- and later blamed entirely for the failure of the first SUM venture. While the plan for Washington was more or less executed, the plan for Paterson was deliberately discarded, and the city's long non-planning tradition begun.

Having disposed of L'Enfant, the SUM imported Peter Colt from Hartford, Conn., to superintend the project. Using the scant beginnings of the aqueduct, Colt built a raceway for more expedient ends -- to give the SUM immediate waterpower, and to put them in business at last. But it was too late for Colt too; his first mill was finished by 1794, not soon enough to save the SUM from near bankruptcy. By 1800, there were several mills, but business was not good and Colt returned to Hartford. In 1814, his son Roswell Colt appeared, acquired control of the corporation, and cashed in on its tax exempt status by leasing out the waterpower and the land. He made a killing, and Paterson went into its prime.

Water power was promptly replaced by steam and eventually by electricity, so the oft-extended raceway and riverfront factories became a background for inland industry; the town grew rapidly and at random. Paterson became the home of the first Colt firearm, the Rogers locomotive, and the majority of manufactured textiles for New York City and Philadelphia.

Despite periodic prosperity, the city of Paterson collected nothing when SUM business was booming and suffered (at about 20-year intervals) when business was bad. But the city was not in serious trouble until the end of the 19th century when the major manufacturers moved to Pittsburgh and to the south, leaving Paterson to live off the leftover light industry and the economic opportunities of nearby New York City.

One happy effect of unsteady success was that Paterson industrialists were rarely able to replace their old factories with completely new models, and the older ones were only occasionally updated. Thus, some of the buildings in operation today date from the early 1800s, and along with those built throughout the 19th century, provide in Paterson a complete catalog of industrial architecture in this country.

If the move of big industry weakened Paterson's already uncertain footing as an eastern industrial power, the influx of immigrants after the turn of the century brought the city to its knees. The increased numbers introduced shortages in housing, jobs and recreation facilities that have never been relieved.

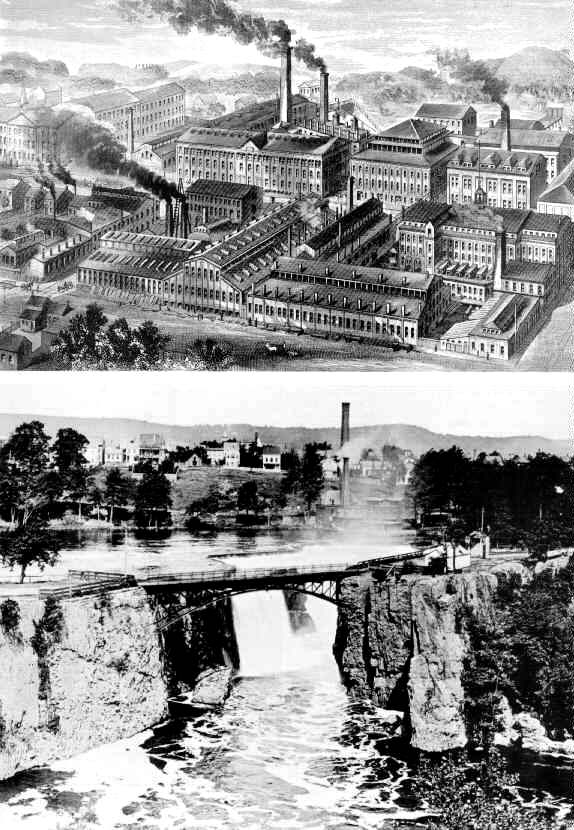

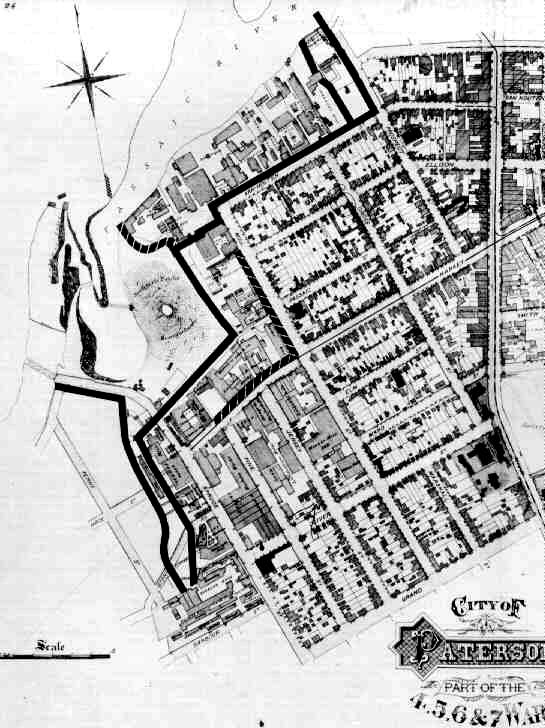

A detail of an 1877 map (above) shows the raceway in its final form. The Urban Deadline drawing (below) shows the same area after the loop of Interstate Highway 20 has been built late 1970s). This route -- which saws off a corner of the oldest part of Paterson -- has been chosen for reasons which include the following two: 1) low density of the industrial district, and 2) lack of opposition from the adjacent residential district, which is to say, the poor will put up with it. Urban Deadline chose the site for the center of a renewal proposal because 1) it is the heart of Paterson's history, and 2) its development may neutralize the effect of the highway and prevent a poor section of the city from becoming another Watts.

Paterson is a town that has always been popular when prosperous, and abandoned when threatened; it is threatened now, but there are people who are proud of the past and want to do something about it. The present mayor, Lawrence Kramer, and Mrs. Kramer are among them, along with a few local historians and a number of other interested individuals.

Kramer's credentials are good: he is a Republican who was elected in 1965, before it was fashionable; he has just been re-elected: and he has not been indicted for anything. But traditionally, the mayor of a city like Paterson occupies a position somewhere between the black man and the unliberated white woman: he is eligible for blame, but not entitled to beg. When Paterson's blacks rioted in 1968, it was prime-time television news, but when Paterson City Hall asks for substantial federal assistance that is no news at all: the requests are filed away, and no one in Washington expects to he criticised because -- as cities go -- Paterson is a second-rate city.

The situation is changing slightly. A Model Cities project is underway; HUD and OEO have programs in job training and education: and private organizations like the Inter-City Christian Action Group, the United Group, and the Catholic Archdiocese are active. But the combined strength of all federal grants to Paterson constitutes little more than a vestpocket attack on a sinking city. Washington has its own problems restoring Pennsylvania Avenue to its original L'Enfant grandeur. Paterson is not the nation's or even New Jersey's capital, and it sent L'Enfant packing before he had a chance to leave any landmarks of great significance.

L'Enfant and his contemporaries, however, may still be the key to Paterson's recovery. Since L'Enfant himself did not leave any evidence of his involvement, the industrial architecture becomes important, historically, as an evolving technological complex. The individual buildings are not distinguished architecturally, but all together along the meandering raceways they are often picturesque and certainly are uncommon.

As yet, the historic buildings have not been noticed by the government agencies charged with protecting America's past. In 1967, the Department of the Interior designated the Great Falls a "Natural Historic Landmark," opposite which a vast and ever-empty parking lot was installed -- institutionalizing the site and almost obscuring the view of the river below -- and in honor of which a bronze Alexander Hamilton was erected to guard the lookout and sport a National Parks Service plaque.

Beyond this, no government agency has responded to the call. Even the Smithsonian Institution's energetic Robert Vogel, who recorded much about the Merrimac Valley Textile Mills in New England (many now demolished to make way for "urban renewal"), was unable to stretch the war-shortened Smithsonian resources to fund a preliminary survey.

The worthiest historic causes seem to need a bulldozer to be convincing as threatened monuments have first priority. But Paterson now has the threat of its own Interstate highway, so application has been made to the National Register in hopes of having the entire site declared an Historic District, and favorable action is expected.

Some time ago, Mrs. Kramer was advised by an architectural historian and restorationist to generate public support for a preservation project, and -- since funds were lacking -- to find someone to do the architectural investigation for nothing.

John Young, who is a member of Urban Deadline, had gone to Paterson in 1967 to examine the industrial architecture as a possible subject for a master's thesis; he was in the M.S. program in Preservation and Restoration of Historic Architecture at Columbia University. Greatly impressed by its potential, he wanted to plan a preservation and renewal project around the old buildings. When a faculty member in the department at Columbia vetoed the subject ("there is nothing there"), Young submitted no thesis. That was the year that Columbia "blew up," and Young joined the student strike.

Remembering his interest, Mrs. Kramer later contacted Young as her possible "good for nothing." She found that in the interim he and some 15 others from Columbia had formed what is now Urban Deadline. The strike was its initial impetus -- the group wished to demonstrate in architectural terms that the insurrection was constructive rather than destructive. Relieved of academic constraints, they soon became involved in community projects, were constituted a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation, and have been active in New York City and elsewhere since the summer of 1968.

Urban Deadliners have been called advocate architects, architectural activists, guerilla architects, and kooks:;they are usually involved in no- or low-budget projects that have been overlooked or rejected by professional architects, or in projects that are vainly awaiting some other kind of expert attention. They have been involved in almost every aspect of traditional architecture, from band-aid maintenance and actual construction on existing buildings, to design and planning for new buildings, camps, and parks. Their work is always done with the people who want it done, and is intended to demonstrate that people are capable of, benefited by, and responsible for "doing their own architecture."

The Urban Deadline project for Paterson begins with a preliminary proposal (which includes the material shown on these pages, and will be followed by research, participatory planning, and implementation. The graphic material and historical reports prepared by John Young were submitted to Columbia in June 1969, and were enthusiastically received by Professor James Marston Fitch, head of the graduate program in Preservation and Restoration of Historic Architecture. Thanks to Fitch, students can explore the curious idea that preservation of historic architecture can result in something more than another Williamsburg, and that restoration can be a basis for urban design.

The historic area is bounded roughly by the raceways and the Passaic River, Paterson's oldest landmarks. Young chose 40 buildings to be restored and preserved -- some will continue to function as factories, others (crippled by the highway) will become community centers, restaurants or factory museums. Amenities now absent have been introduced, and some historical precedents revived. Much of what Young has proposed is not unheard of -- he has concentrated on the city's current problems, and taken into account the fact that Paterson will probably not be selected for outside assistance, and that any plan for improvement will have to come from the people inside. So he has not tried to create anything that is too fancy; he has illustrated that the people can turn their history into part of a renewal plan for the future, for their own use and pleasure.

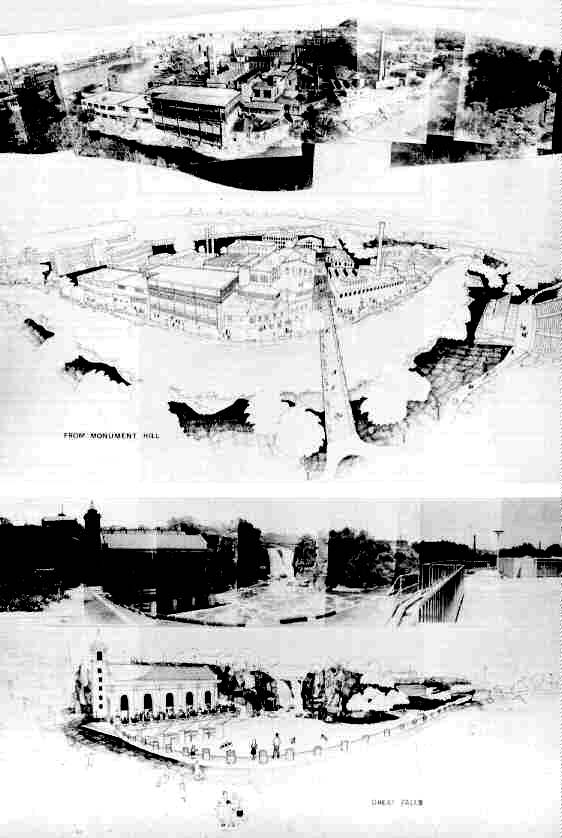

One of his ideas is to build a bridge below the falls and restore the 19th-century situation of a public park on the riverbank opposite the factories. The drawing from Monument Hill (below, top) shows the development of both sides of the riverfront; the bridge leads from the factories to an amphitheater or other facility that would encourage public use of what is now a dumping grounds. The spot is also easily reached by residents of the Fifth Ward, which is in an isolated section that will he completely cut off unless an attractive connection links it to the other side of the river.

The borders of the raceways would become a park. The thicket around the raceways is already popular for those who are willing to venture in -- to play in the water or sniff glue in the bushes. The thicket needn't be disturbed, but it can be made accessible to more people. The view from the Ivanhoe Works (right) takes in two Levels of the raceway -- but it is now taken in only by those willing to scale the bank and stand knee-deep in the upper race staring at what looks like an open sewer. Young's drawing shows what this might be if opened to the public as part of a meandering path along the raceways.

Ideas like these are not intended as final designs; they are intended to inspire the people who will be making the decisions and who will be planning what will be the design -- the people of Paterson. "Urban Deadline's role," says Young, "is to be the advocate and investigator of a process of planning that must be carried out by the groups who will be affected by the project." From now on, Urban Deadline will operate only in certain situations: 1) they will see that the ideas of all groups are heard, given graphic form, and then integrated into the project; 2) they will present the project to all groups, outline its potential development, and describe the process that can be used to carry it out; and 3) they will identify and evaluate sources of funds, public and private.

The rest will be the work of the people. The historical research will proceed, and the real research will begin. That is, the Patersonians who know about the project will contact the people who are to be affected, and begin to collect ideas. This is the most delicate part of the operation, for as Young says: "It has components that could appeal equally to all contending factions: low-, middle- and upper-income. It is not just architecture.,or historic preservation, or beautification, or housing, or job training; nor can it become a political football to be kicked around by various factions. It is necessary that all participate who will be affected by it."

Urban Deadline sees Paterson as a New York storefront, with which they have had much experience, writ large. They know that it is possible to take an abandoned building and make it work again, once it is accepted as given -- you can't count on a new one, so you think in terms of what's there -- and make the most of it. Paterson is a city, not a storefront, but it is not a huge city. With a population of 150,000 it is not big enough to have a slick City Hall that runs things by remote control, but it is not small enough to be without political suspicion. It is big enough to have to contend with the same problems that plague the biggest cities, but too small to warrant major federal or state attention. So, no matter how presentable and traditional its structure, it cannot manage in a traditional way, and it will have to hustle what major cities can demand.

"Clearly," says Young, "the major hurdle is the resistance to be found in most groups to proposals that they have not begun themselves. Urban Deadline thinks that this resistance is justified with respect to most projects coming from groups with special interests." He adds that Urban Deadline has already been told that the project will be rejected if it comes out of City Hall. So it will be Urban Deadline's responsibility to generate interest and public support for the project, because they are less suspect politically than City Hall. They aren't on anybody's payroll.

Urban Deadline believes that their storefront discoveries can be extended to Paterson, in spite of the scale, because it involves the same process. "It might be called advocacy architecture," says Tyler Smith, of Urban Deadline, "but that is too narrow. It goes beyond architecture to the politics, sociology, and economics that establish the preconditions of architecture.''

The process begins to work when every faction is notified that it can be heard, and the planning begins when they are satisfied that they have been heard. Implementation involves all the experts, organizations and conventional schemes that need to be brought into the process in order to execute the plan -- once the plan is such that no one can walk away with it.

First, though, Paterson must accept itself as given and must see what it has to get by with. Its industry was once its fortune, and the remains may be a new key. "Paterson's history gives the city an understanding of how it evolved and where it is going," says Joel Silverberg, an Urban Deadliner. "It gives it a place to re-evaluate its existing resources, and it becomes a symbol which can be expanded into something concrete for the future.''

This is not a sentimental attempt to retrieve another era. It is an attempt to unbury the past in order to telescope the events that have led to the Paterson of today, and remind the people of Paterson that the present will not be the last chapter of Paterson's history.

John Young's drawings -- below photographs of present Paterson scenes -- show some possibilities for the old industrial area. Here (above, top), Monument Hill is the site of a public amphitheater and a hillside park; the factories open onto a riverwalk, much like the celebrated version in San Antonio, Tex. The Power Station (above, bottom), built by the SUM in 1912, is an indoor-outdoor restaurant with a fine view of the Falls above and boaters below.